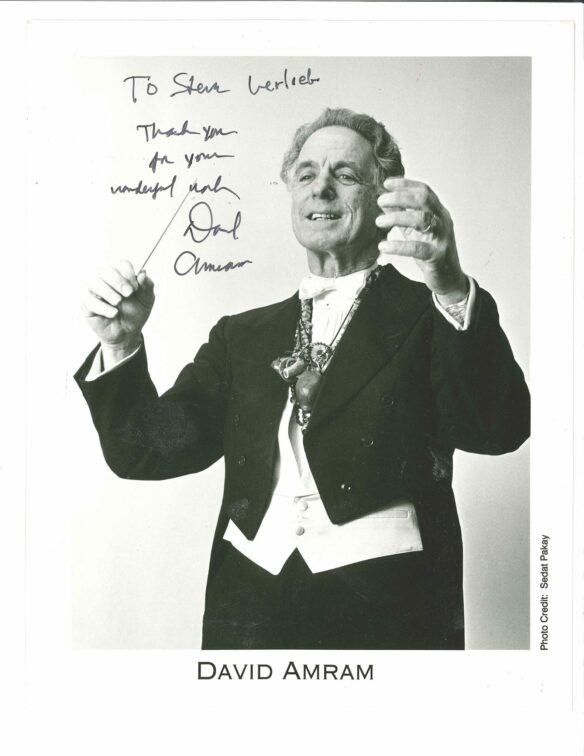

By Steve Vertlieb: It had been a dream of mine for fifty-five years to finally meet iconic film composer David Amram. This ninety-one-year-old powerhouse classical, jazz, and motion picture composer is among the last of a remarkable breed.

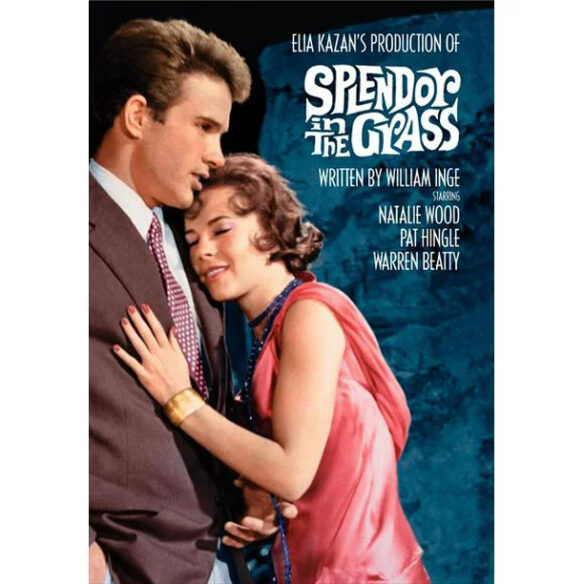

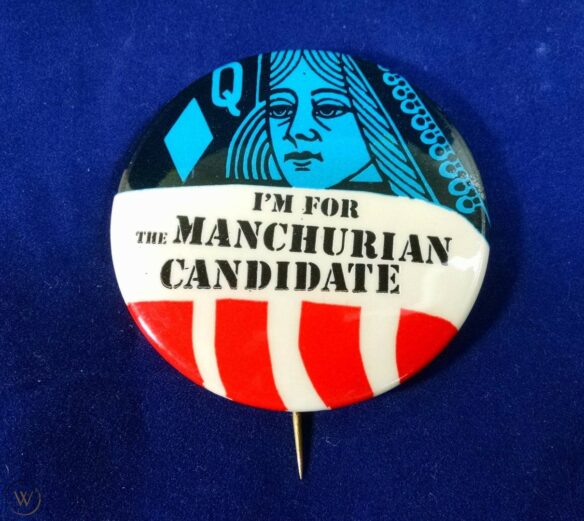

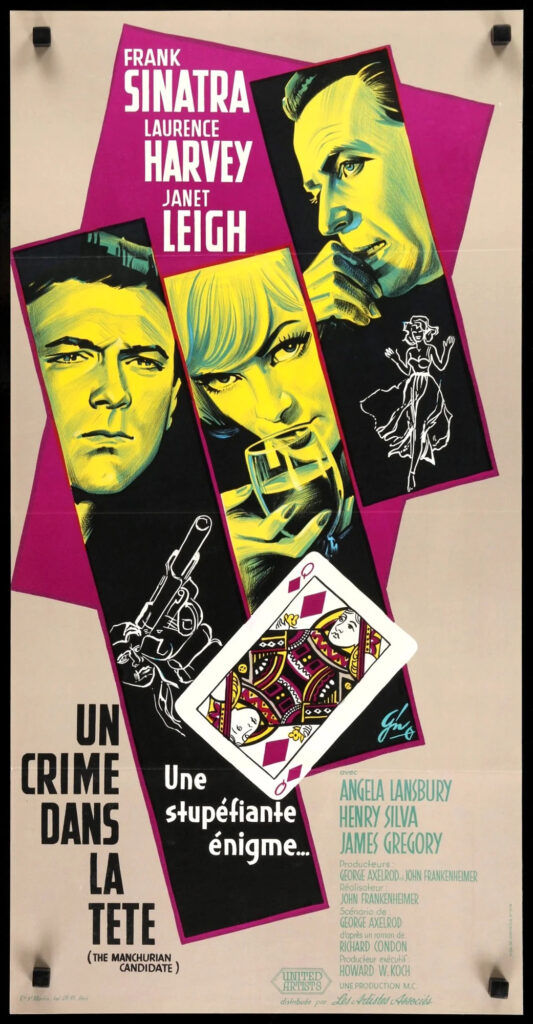

Still composing and performing all over the world at his rather tender young age of ninety-one years (on November 17 last year), David is the composer of such original motion picture scores as The Manchurian Candidate (with Frank Sinatra, Lawrence Harvey, Janet Leigh, and Angela Lansbury ) for director John Frankenheimer, Splendor In The Grass (starring Natalie Wood, and Warren Beatty) for Elia Kazan, and The Young Savages (with Burt Lancaster) once again for John Frankenheimer.

David harkens back to an artistic period during the 1950’s when the world was still young, and brash enough to believe that anything was possible. As part of the “Beat Generation,” David worked closely with Jack Kerouac, composing music for some of the author’s early films, as well as emigrating to Hollywood to write for some of the most distinguished film productions of the early 1960’s. A student of many diverse cultures and influences, including Native American, David is truly a man for all reasons and seasons.

Among his countless friends over half a century could be counted Frank Sinatra, Marlon Brando, Paul Newman, and Pete Seeger to name just a selected few. David and I had corresponded, and spoken on the telephone, for the past several years, but had never actually had an opportunity to personally meet.

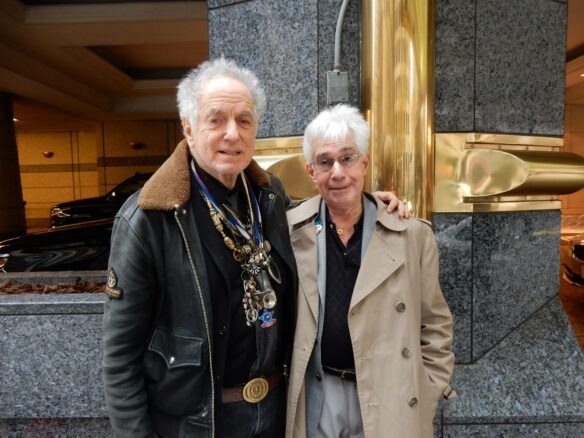

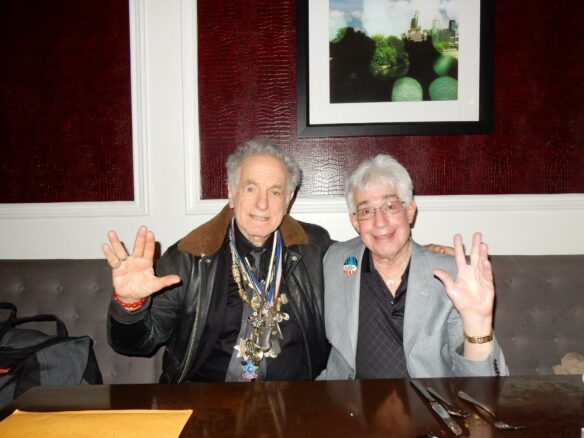

When David visited his home town of Philadelphia in early December, 2016, for a concert of his music, he invited me to join him for lunch the following day at his hotel….and so, on Thursday afternoon, December 8 of that year, David and I shared an absolutely joyous two-hour repast at The Weston Hotel in downtown Philadelphia. He regaled me with stories of his remarkable career, and made me feel that we had known each other for decades.

During these difficult days and years of dissension, insecurity, and intolerance, it was somehow reassuring to share such precious hours and memories with a cultured, gentle, musical inspiration from another time and, sadly, ideologically distant artistic reality.

When we parted, David hugged me. As we embraced, I told him that I loved him, and he responded in kind. This was truly among the happiest experiences of my life, and I remain both flattered and honored to think of David Amram as my friend.

DAVID AMRAM, CINEMA’S ELUSIVE MUSICAL POET

[First published in 2017.]

David Amram remains one of America’s most profoundly expressive composers. Like Leonard Bernstein, who appointed him as the first composer in residence for the New York Philharmonic, Amram refused to be pigeonholed or labeled by a single genre or musical style. He has written opera, classical, folk, jazz, Native American, and motion picture music. Of the latter, it can safely be stated that the least is known. Amram’s first film score was for Echo of an Era a documentary motion picture produced in 1956 about the dismantling of New York City’s third avenue elevated subway line.

In 1958, director Elia Kazan asked the composer to write the music for his Broadway production of J.B., a play by Archibald MacLeish, written in verse and based upon the biblical “Book of Job,” winning a 1959 Pulitzer Prize for drama. He began scoring short films during the “Beat Generation” for his friend and colleague, Jack Kerouac, in 1959 with Pull My Daisy. Kazan approached Amram once more in 1959, asking him to score his upcoming film for Warner Bros., Splendor in the Grass. William Inge had worked on a treatment of the story with Kazan, turning the treatment into a novel with the clear understanding that Kazan would turn it into a film. Although the director wanted Amram for the picture, he was required by Jack Warner to produce Amram for an informal interrogation by the studio head. Warner was unhappy with Kazan’s choice of David as the composer since Amram had few theatrical credits to his name. Kazan reminded Warner that neither Alex North on A Streetcar Named Desire nor Leonard Bernstein with On The Waterfront were particularly well known at the time that they worked for the director, and that neither composer had done too badly with their respective careers in the intervening years. Amram was eventually hired by the studio to write the score, but the music publisher assigned to the film complained that the composer’s score “had too many chord changes,” and that it “would never produce a hit song.” Additionally, he said that the score was simply “too weird.” Consequently, the studio decided not to release a commercial soundtrack album of the music when the film was released in 1961. Despite hesitation on the part of Warner Bros, Kazan adored the score. Lush, romantic, and heartbreakingly evocative, Amram’s score for the coming of age drama about a young woman tormented by fear, and frustration over her burgeoning sexuality, is exquisite. Its hauntingly beautiful theme, echoing the lonely melancholia of a young woman on the terrifying brink of mental collapse, is simply unforgettable, contributing immeasurably to the deep sadness and poignant clarity of Natalie Wood’s Oscar nominated performance

While working still on Splendor in the Grass for Kazan, John Frankenheimer asked Amram to compose the music for his new film concerning violence in the streets, and juvenile delinquency. The Young Savages, directed by Frankenheimer and starring Burt Lancaster, was a defiant condemnation of societal prejudice and urban violence, and featured an explosive dramatic score by Amram, utilizing powerful latin and jazz motifs expressing the hopelessness and fear rampant in New York’s ghetto neighborhoods.

However, it was for director John Frankenheimer once again that the composer would write his most important motion picture score, The Manchurian Candidate in 1962. Based upon Richard Condon’s best-selling novel of brain washing during the Korean War, the often shocking, experimental tenor of the film cried out for a decidedly non-traditional composer and score. Frankenheimer’s documentary approach to the film, combining contemporary lensing with explosive interludes of pure cinema verite and newsreel simulation, required a fresh, wholly original avant garde soundtrack. Amram’s extraordinary work on the motion picture has easily stood the test of time in its power, intensity, and quiet eloquence. The main title sequence, a subtle elegy for strings, is a remarkably elegant prelude to the sobering thematic story line. It is a haunting, reflective melody played with subtle power and authority throughout the film, conjoined at pivotal moments by a brooding solo horn, adding to the intense, yet melancholy nature of the unfolding tragedy.

Composed by the then thirty one year old composer during the Spring of 1962, the score for The Manchurian Candidate is a brooding, portentous tone poem, deeply evocative at its core, yet entirely menacing in its understated performance. Director John Frankenheimer had reportedly gone to a production of New York’s Shakespeare In The Park series, and listened to portions of the incidental music written by Amram for the productions. This, according to the liner notes for the belated soundtrack recording, led directly to Frankenheimer hiring the composer to pen the score for his Emmy Awarded television production of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, which starred Ingrid Bergman in her television debut for Ford Star Time on October 20th, 1959. Frankenheimer’s only significant instruction to Amram for scoring The Manchurian Candidate, was to “pay attention to the film.” “The picture,” he advised, “will tell you what to do.” “I hired you because you’re different from anyone else, and you care and have pride in what you do.” Upon completion of his score for the film, producer and star Frank Sinatra remarked that “David Amram has done a magnificent job. The score is exactly what I wanted for the film. The music is almost sane sometimes, as the story is almost sane sometimes. And at other times, the music is in the trees, just like the movie. It is a great score.” John Frankenheimer commented in 1997 that “David Amram’s haunting score drives the movie forward and emphasizes perfectly all the dramatic elements.” Amram’s recording sessions for the soundtrack were completed during four separate sessions over two days, utilizing symphony soloists, chamber music performers, as well as both jazz and Latin musicians. Manny Klein performed the unforgettably searing trumpet solos for the film while, according to the CD’s liner notes, Amram’s enthusiasm and energy were boundless, conducting the ensemble for the recording and jumping into the sessions himself with wholly improvised solos on French horn and piano. Most tracks, reportedly, were completed in a single take.

Sinatra and Amram had never met during the making of the film, nor did they meet during the scoring sessions, but Sinatra deeply admired the music. Early in 1963, David Amram was appearing at the Village Gate in New York. Actor Martin Gabel approached him after a set and said, in his characteristically gruff voice, that “Frank is waiting downstairs to meet you.” Naively, Amram asked “Frank Who?” Startled by his friend’s innocence, the actor bellowed “SINATRA.” Sinatra was cordial and warm, expressing his admiration for The Manchurian Candidate score, while exclaiming his astonishment that the soundtrack had never been released to the public. Years later, Tina Sinatra produced a three-track recording of the soundtrack from her safe, and the score was finally released on CD decades after it had been produced. Frank Sinatra, Jr. wrote in the accompanying liner notes that “The ingenious combination of polytonality and jazz was just incredible to me, and the choice of instruments was perfect for the film. None of us had ever heard a film score like this before.”

John Frankenheimer next turned his sights to directing Seven Days in May, a political thriller concerning the attempted overthrow of the United States government by a covert military coup. With a screen play by Rod Serling, and a powerhouse cast of actors that included Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas, Fredric March, and Ava Gardner, Frankenheimer asked Amram once more to compose the music. The score was written and recorded, but executive producer Edward Lewis disliked the music, and replaced Amram with Jerry Goldsmith who wrote a brief fifteen minute track utilizing percussion and piano. David Amram’s score was forever lost, while not even the composer has any memory or physical remnant of its content.

The Boston Globe once referred to David Amram as “The Renaissance man of American music.” Composer John Williams wrote that “I have always regarded David Amram as one of the greatest composers of the twentieth century, and I don’t just mean for the cinema.” Now, thankfully, his music is receiving the exposure that it so rightly deserves.

++ Steve Vertlieb — February 2017