By Cora Buhlert: As a reader and writer, I like stories that cross genre boundaries. Therefore, the anthology Terror at the Crossroads – Tales of Horror, Delusion, and the Unknown sounded like something right up my alley.

By Cora Buhlert: As a reader and writer, I like stories that cross genre boundaries. Therefore, the anthology Terror at the Crossroads – Tales of Horror, Delusion, and the Unknown sounded like something right up my alley.

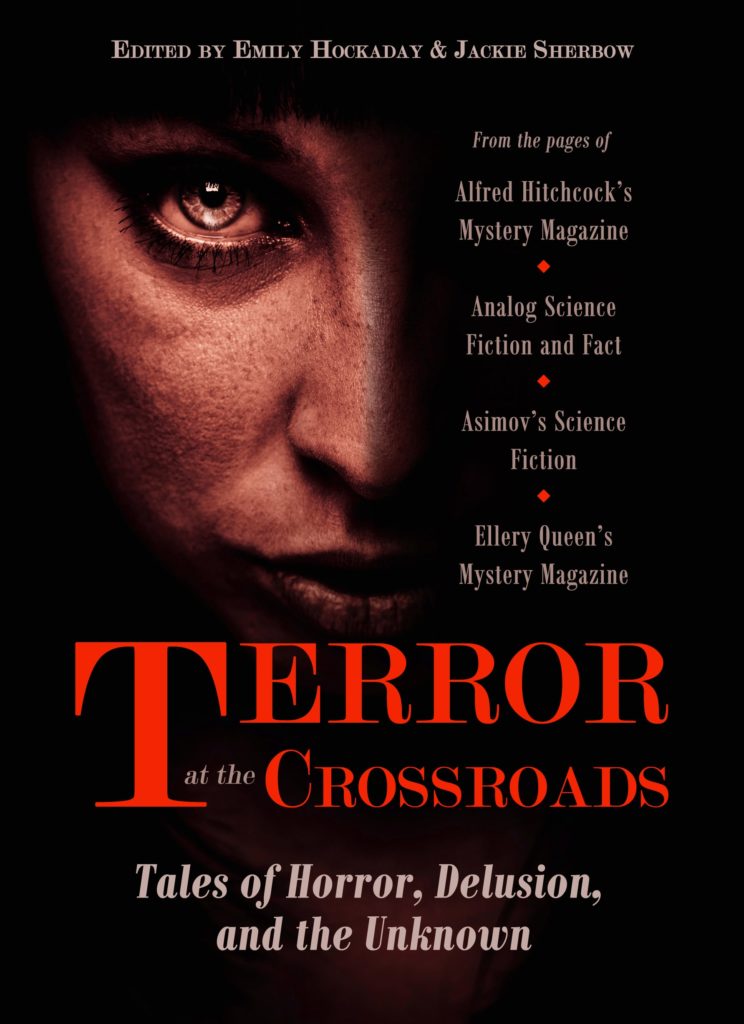

Editors Emily Hockaday and Jackie Sherbow have combed the pages of Dell’s stable of fiction magazines, i.e. Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, Analog Science Fiction and Fact, Asimov’s Science Fiction and Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, and assembled a wide range of stories that sit at the intersection between mystery and crime fiction on the one hand and science fiction, fantasy and horror on the other. All stories were originally published between 2010 and 2017.

Now I am somewhat familiar with Analog and Asimov’s, though I’m not a regular reader of either magazine due to the difficulties of getting hold of them in Germany. Alfred Hitchcock’s and Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, however, were completely unfamiliar to me. I know that they exist, but I have never read a single issue of either mag. That said, I am an avid reader of short mystery fiction, albeit mostly in German. And in Germany, the genre we call “Krimi” is a lot broader than the US mystery genre and encompasses not just mysteries, but also crime fiction, thrillers, suspense and noir. Therefore, I was pleasantly surprised that the stories in this anthology that originated in the two mystery magazines were a lot more varied and experimental than the rather narrow definition of “mystery” in the US sense as “a story about an investigator solving a crime, usually a murder” would suggest.

Quite the contrary, traditional whodunnits were definitely in the minority, even among the stories that originated in the two mystery mags. “Monsieur Alice is Absent” by Stephen Ross, in which a young trainee teacher suspects her more experienced colleague may be a serial killer and sets out to prove it, is probably the closest this anthology gets to a traditional murder mystery. Meanwhile, “Exposure” by A.J. Wright might have been a classic whodunnit under different circumstances. After all, there is a murder, linked to another unexplained death decades ago, and there even is a massive red herring. But instead of following the investigator as they solve the case, we view the events through the eyes of a teenager who is connected to both the victim, the murderer and the unexplained death that links them.

Other stories fall under the broader crime fiction umbrella and tell how and why a crime was committed. The best of these is probably “The Widow Cleans House” by Jason Half, which tells the story of failing relationship, where the fact that a crime was committed only becomes clear at the very end. In fact, most of the crime stories in this anthology involve murders committed inside families and relationships. Other examples are “Pisan Zapra” by Josh Pachter, “Alive, Alive-Oh!” by O.A. Tynan and the above mentioned “Exposure” by A.J. Wright. Coincidentally, all of these stories are straight crime fiction without any speculative elements.

There also are a number of supernatural crime stories such as such Zandra Renwick’s “A Good Thing and a Right Thing”, where a psychic at an archaeological dig witnesses a centuries old crime. In Barbara Nadel’s “Nain Rouge”, a man hunts a folkloristic imp across the ruined cityscape of Detroit. The conclusion is truly chilling, in more ways than one. Meanwhile, Kathy Lynn Emerson’s “Lady Appleton and the Creature of the Night” is a delightful murder mystery turned werewolf tale set in Elizabethan England. Kit Reed’s fine story “The Outside Event” starts off as a pointed look at the cutthroat rivalry at an exclusive writing retreat, where the narrator’s fellow writers mysteriously vanish, and then turns into a tale of gothic horror halfway through. And in some stories such as Tara Laskowski’s “The Monitor”, a meditation on the stress and fears of new motherhood and the ambiguous feelings of a woman towards her newborn child, there is no crime at all, just a pervading sense of dread.

As might be assumed from an anthology drawn from such a broad range of sources, the settings of the stories vary widely in time and space from Viking Greenland and Elizabethan England via several contemporary or near contemporary Earth settings to a nameless planet in the far future. Even the contemporary and near future Earth stories don’t all share the same familiar US/UK settings. No, there are also stories set in Canada, Ireland, France, Spain, Greenland, Turkey, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea. Though only one story, “Still Life No. 41” by Catalan author Teresa Solana, was originally penned in a language other than English.

It’s also notable that many of the stories set outside the English-speaking world nonetheless feature British or American protagonists. What is more, a few of these stories carry an unpleasant whiff of colonialism. In some cases, this is intentional such as with Josh Pachter’s “Pisan Zapra”, which traces the revenge of an expat woman in Malaysia on her cheating husband. Hereby, Pachter manages to capture a certain type of self-centred western expat in South East Asia, for whom the locals are invisible except as servants or lovers, very well. At any rate, the story immediately reminded me of the time I spent in Singapore as a young girl. And yes, the bored expats holed up in their country clubs are just as unpleasant in real life as they are in this story, though the expat wives I encountered never resorted to murder (and neither did their husbands), but instead came crying to my mother about their wayward husbands.

On the other end of the scale is “The Empty Space” by Kurt Bachard, a story about a trio of selfish English people visiting a Turkey that is pure Orientalist cliché and seemingly populated only by fakirs and dancing girls. If not for a brief mention of air travel, the story might just as well have been set in the days of the Ottoman Empire, though the depiction of Turkey would have been a cliché even then. The protagonists of “The Empty Space” are so unpleasant (and not deliberately as in “Pisan Zapra”) that you do not care when something awful happens to one of them.

In fact, self-absorbed, whiny and downright unpleasant protagonists are a problem with several of the stories. Examples include “The Empty Space” as well as Teresa Solana’s “Still Life No. 41”, whose museum curator protagonist comes across as a spoiled brat who only cares about her career, even in the face of a dead body appearing in the very museum where she is working. “Alive, Alive-Oh!” by O.A. Tynan features a failed writer as the protagonist, who is not only a stereotypical entitled white man, but who also literally gets away with murder and is subsequently rewarded with an adoring girlfriend and the second bestseller he craves. The story might work, if it were satire, but I fear it isn’t. “Notes Towards a Novel of Love in the Dog Park” by Louis Bayard is another story with an unlikable writer protagonist (in fact, entitled writer and artists are something of a theme in this anthology), who has nothing better to do than stalk a random couple she sees in the park and plot revenge upon them when it turns out that they are not what she wants them to be.

Quite a few of the stories in this anthology use unusual narrative structures and experiments with form. Megan Arkenberg’s “Final Exam” is a clever story which recounts the intertwined stories of a failing marriage and an invasion by shambling Lovecraftian horrors in the form of a multiple-choice test. The amusing “Lonely Hearts of the Spinward Ring” by Paddy Kelly is told in personal ads, while David Brin’s “Crysalis” is a collage of laboratory reports, interview snippets and literary quotes. Meanwhile, Louis Bayard’s “Notes Towards a Novel of Love in the Dog Park” takes the form of a writer’s brainstorming notes. And Kit Reed’s “The Outside Event”, yet another story with a writer protagonist, combines snippets from the writer’s unfinished novel with messages sent to her boyfriend and confessional tapes in the style of certain reality shows to tell a story of gothic horror at an exclusive writing retreat.

But the best of the stories that experiment with form is Will McIntosh’s “Over There”. The premise is that three graduate students of physics conduct an experiment and manage to split reality in two. From the moment of the split on, the story continues in two columns which recount events “over here” and “over there”. Eventually, both strands combine again for the devastating conclusion. “Over There” is not a pleasant story at all and the ending is a true gut punch, but it’s probably the strongest story in this anthology. At any rate, it’s the one that stayed with me the longest.

Another unsettling story that crosses over into horror territory is “The Deer Girl Hitches a Ride” by Seth Frost, a disturbing road trip across a post-apocalyptic America, where the titular deer girl is not the strangest or most terrifying thing the protagonist encounters. Meanwhile, Rachel L. Bowden’s “The Persistence of Memory” follows two outsiders on the cusp of adolescence in a story that feels very reminiscent of Stephen King’s “The Body”. There is a science fictional twist as well – after all, this is an Analog story – but it feels tacked on.

As always with such anthologies, there are some stories that just don’t work. Sadly, most of them are science fiction. One example is “Day 29” by Chris Beckett. The story is chock full of great ideas and fascinating worldbuilding details, but eventually goes nowhere and even wimps out of a dark turn of events that seems to have been set up previously.

Meanwhile, David Brin’s “Chrysalis” is exactly the sort of story that gives hard science fiction a bad name. It’s basically a biology lecture, complete with cardboard thin characters and jargon-laden “As you know, Bob…” infodumps, in search of a plot. When it finally finds one, the plot is a hoary old “Thou shalt not mess with things man was not meant to know” chestnut that has been with our genre since Frankenstein. Alex Nevala-Lee’s “Cryptids” is better at combining biology and fiction, though in the end the story is still too long and once again turns out to hinge on a very old genre trope indeed, in this case the idea that prehistoric animals have somehow managed to survive in secluded parts of the world.

All in all, this anthology is a mixed bag with some excellent stories, plenty of mediocre ones and a handful of truly bad ones. If you like both science fiction, fantasy and horror as well as mystery and crime fiction and stories that combine those genres, you’re sure to find something to enjoy here.

Cora Buhlert is a teacher, writer, translator, and reviewer living in Bremen, Germany, the city where she was born. She has a Master’s Degree in English, and has taught English linguistics, technical English, and high school English to German students, in addition to performing translations of technical documents. The author of speculative fiction, crime fiction, romance, poetry, and nonfiction, she blogs about her own and others’ works at her website.