By John Hertz: In one of Forry Ackerman’s more inspired puns, he called us the Imagi-Nation.

We make things up.

Of course all art does. Maybe all life does.

I knew people with a bookshop that had two names, “Bookfellows” and “Mystery and Imagination”. I told them I liked “Bookfellows” better because all books were mystery and imagination.

SF is particularly hard. If it’s just like what we already know, it’s only mainstream. If it’s too unlike what we know, how are we going to engage with it?

I’ve mentioned C.S. Lewis’ advice I call the One Strange rule: ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances, or extraordinary people in ordinary circumstances.

Ambitious SF authors may try both.

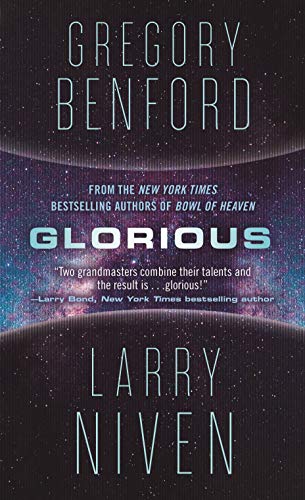

Glorious, the Greg Benford – Larry Niven novel appearing last year, is one of the more ambitious SF stories. It’s third in a series. I didn’t re-read the first two before reading it. I don’t think you’ll have to.

It’s an interstellar-travel book. To manage that, some authors make up a way to go faster than light. So far as present-day science knows, it can’t be done (yes, I’ve heard of the Alcubierre drive; even if it’s possible we can’t build it now). There’s no faster-than-light drive in Glorious. There are no generation ships. There’s suspended animation – “cold sleep”. The authors don’t suppose that will be easy or simple. There’s a lot of high-power computing machinery – artificial intelligence.

I don’t know if AI, cold sleep, or FTL will prove achievable. A century or a millennium from now any might have been demonstrated to be fantasy. Meanwhile a story treating any well is science fiction.

Some of Glorious might contradict some people’s religious faith. That faith might be right and Glorious wrong. But faith – I have some – isn’t science. It isn’t less valid – or so I believe – just different. Science is based on things that can be detected and measured in certain ways. Faith doesn’t have those limitations – so it has other limitations. I happen to believe some of Glorious is wrong. But I don’t read books to be agreed with.

Colonists in Glorious think they’re high-tech. They’ve left Earth, and found what looks like a suitable place far enough away. It would be only a short hop in an E.E. Smith book, or a Larry Niven Known Space book, but this isn’t one of those.

Colonists try to prepare for surprises. History shows and SF tells they’re surprised anyway.

People in Glorious get downloaded – if I were writing a few decades ago I’d have had to explain that – into bodies and even machines. That’s almost trivial – I did say almost – compared to what these colonists have to face.

They also have to find how to perceive what they’re facing.

We’ve had stories like A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court with protagonists on the high-tech side. Oh, look at those benighted creatures over there. In Glorious the sucker is on another tentacle.

There’s some reason to believe the Glorious protagonists are being played for suckers.

Benford is known for imagining physics. Niven is known for imagining aliens. Plenty of both in Glorious. There’s poetic writing too. It isn’t quite like either of them. This is a collaboration.

The landing team arrives. We’re a quarter of the way into the book.

The long meadow before them lay quiet and placid.

No greeting party.

No sign of any reception at all.

Not what any of them had planned.

…. a forest that seemed a writhing mass of wide, hollow limbs. Every living thing seemed endowed with light, airy mechanics. Translucent spiked leaves wove in an easy breeze, and diaphanous flowers of a shiny blue and golden yellow…. Beth knew that this plain was underpinned by struts, and so was clinging to a silvery tether trellis [p. 119].

Things will get more beautiful and more strange.

In another ambitious feature of this book, it has illustrations. The graphic artists are Don Davis and Brenda Cox Giguere. That hasn’t been an ordinary part of novels for adults in quite a while. The pictures are monochrome. They aren’t captioned. Like the words, they result from and invite imagination. I thought this had better not go without saying. Getting there took me a while.

Much farther along an alien being says,

“You have encountered our transmitter, which distorts space-time. You correctly deduce that we use this channel to speak with distant minds that carry out large, powerful experiments.”

“Look,” Viviane said, “we came here to communicate and colonize, if you will be so kind. Not about physics and such, at least not right away.”

Redwing whispered to her… “Let Twisto go on. It wants something from us [p. 354].”

If the space – land-space – or something – isn’t unoccupied, and if the people (“Science fiction is about people. Some of the people are aliens”) are higher-tech than our protagonists, how can colonization be possible – if they will be so kind? Must our protagonists, or anyone, be careless, arrogant, or worse?

There’s glory for you.