Past Worldcon chair and Hugo-winning fanzine editor Earl Kemp (1929-2020) died February 6 at the age of 90. The news was only recently shared by his son, Erik Kemp. Earl died from injuries suffered in a fall: after getting up from his computer, he fell and struck his head on the corner of his desk.

Although fandom was a small pond in the Fifties and Sixties, Earl was a very big fish in it. He worked hard to be a mover and shaker, and to circulate among its top writers.

Earl had been born in Arkansas and later moved to Chicago, where he worked in a job printing shop and learned typesetting and book composition techniques for offset printing.

After exchanging a few letters with Mari Wolf (who was conducting “Fandora’s Box” for William Hamling’s Imagination), she connected Earl with local Chicago fan Ed Wood, which led to Earl joining the University of Chicago Science Fiction Club in 1950.

He attended his first Worldcon when it was held in Chicago in 1952. Earl later said, “It was like walking into a world I had been seeking for a very long time. I felt, instantly, that I was at home at last and among my kind of people.”

Earl would become president of the University of Chicago Science Fiction Club and hold office for almost a decade (although the university was told a student’s name for that purpose.) Meanwhile, he chaired two unsuccessful bids to return the Worldcon to the city. As they say, the third time is the charm: he served as chairman of the 1962 Worldcon, Chicon III.

In 1955, Earl and several other UofCSF Club members started Advent:Publishers with the idea of bringing out critical works about science fiction. Advent’s other founders, besides Earl, were Robert Briney, Sidney Coleman, James O’Meara, George Price, Jon Stopa and Ed Wood. Damon Knight had written a goodly number of critical essays for science fiction magazines by then, and it was Earl’s idea to assemble them into a book. In 1956, Advent published as its first book Damon Knight’s In Search of Wonder. Advent would also publish major nonfiction works such as James Blish’s The Issue at Hand, Don Tuck’s massive bibliographic Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy to 1968, Robert Bloch’s The Eighth Stage of Fandom, as well as Harry Warner, Jr’s All Our Yesterdays and Alexei Panshin’s Heinlein in Dimension.

Earl said in one autobiographical comment, “[By] 1959 I was a reasonably well known science fiction fan, collector, bibliophile, pain-in-the-ass wannabe something significant. By that time I thought I knew absolutely every single person of any consequences involved with science fiction, and they knew me.”

Alexei Panshin sketched Earl’s character in these terms in “Oh, Them Crazy Monkeys!”:

…Earl’s strength was his ability to always think of the next thing to do, and then draw other people into wanting to play the game with him — very much in the same way that he’d propose writing a book on Heinlein to me, and then convince me to write it so Advent could publish it.

I described the Earl of those days this way in “The Story of Heinlein in Dimension“: “He was a doer, not only full of bright ideas, but also able to bring them to fruition. A typical Kemp project had an element of originality, called for a lot of work, but yielded results that only imagination and effort could achieve.”

In the copy of the essay which Earl read and then returned to me all marked in red, he inserted the phrase “by a lot of people” after the words “a lot of work” in the previous sentence. That’s an important addition. It emphasizes the group nature of these endeavors. They weren’t undertaken for personalistic Crazy Monkey reasons, but rather for the sheer fun of doing them.

…On the other hand, Earl Kemp’s greatest weakness was that he had the demands of his own Crazy Monkey to contend with. He aimed to get ahead. He wanted to be a success. He longed for recognition. He wanted to rub elbows with the rich and powerful. He wanted to be a player.

The reality, however, was that Earl had a living to earn at a job he didn’t always like, working as a graphics artist for a printer. He couldn’t help thinking that he was capable of more demanding work and of exercising greater responsibility, and he wanted to better himself.

In 1963 Kemp edited The Proceedings: CHICON III, published by Advent:Publishers. The book included transcripts of lectures and panels given during the course of the convention, along with numerous photographs.

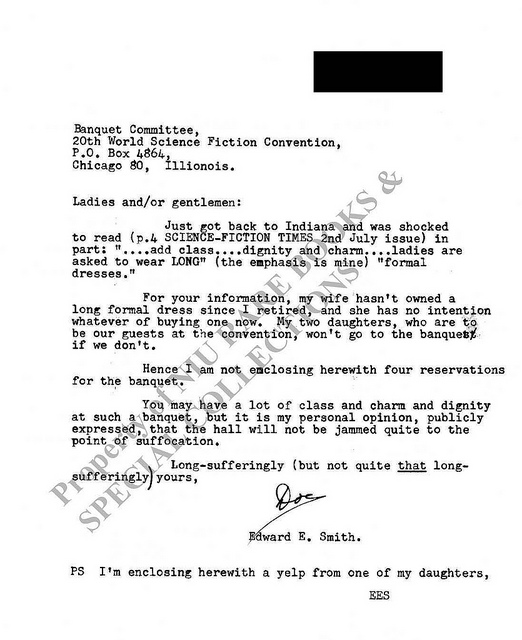

Earl’s work as Worldcon chair gained fresh notoriety in the last decade when NIU posted an online exhibit of correspondence related to the 1962 Chicago Worldcon, including his invitation to Isaac Asimov to deliver a pseudo-lecture on the theme of “The Positive Power of Posterior Pinching”. (The suggested pseudo-lecture did not occur.) The exhibit was the basis for Stephanie Zvan’s 2012 post “We Don’t Do That Anymore”, the point of which seemed to be missed by Earl, who left a comment: “What a wonderful find. Thank you very much for posting this. It’s nice to be reminded of some of the good things. I admit I’ve forgotten this, but it certainly was Ike.”

He was a prolific fanzine editor, who won the Hugo Award for Best Fanzine in 1961 for his publication Who Killed Science Fiction? It was a classic Kemp project, edited with his then wife Nancy Kemp (1923-2013). To create the fanzine, “Earl sent the same five questions to 108 people, the elite of the science fiction world. And he printed the seventy-one responses he received.” Robert A. Heinlein participated, but insisted on being listed as an anonymous respondent. Who Killed Science Fiction? was distributed through the Spectator Amateur Press Society (SAPS), a long-running amateur press association.

In December 2006, Earl released the “complete and unexpurgated” text of Who Killed Science Fiction? as a webpage on eFanzines. The first question reads —

1) Do you feel that magazine science fiction is dead?

YES: 2

NO: 55 replies, of which 38 qualified their “no” by following it with “but…,” and an alarming percentage of these 38 indicated that the death struggle was already in sight.

YES: Eleven replies, stating either “yes” or definitely dying already (this figure includes my personal vote).

After Earl won the Hugo, Heinlein seems to have regretted not putting his name on his reply.

In Seattle in 1961, after I had been awarded the Hugo for Who Killed Science Fiction?, Robert Heinlein approached me. He had this deliberately calculated way of insulting through faint praise; his words would flow out of him effortlessly as if he had spent some time rehearsing them, perhaps saying the words aloud to himself.

“If I had of known what a good job you would do with Who Killed Science Fiction?” he said, “I’d have allowed you to use my name in it.”

Gee, thanks, Bob? I believe that was the closest I ever came to receiving an apology from Robert Heinlein

The Hugo win spawned some controversy among those who felt it was wrong for the award to go to a publication that only had a single issue. The eligibility rules for fanzines soon were changed to prevent the recurrence of a one-shot winning. The requirement for a fanzine to be “generally available” may also have been inspired by the zine having been distributed through a members-only apa.

Earl produced a number of other fanzines up until 1965, including Destiny and SaFari. After a 37-year break, he returned to editing fanzines with e*I*, which focused on Earl and his friends’ memoirs of the science fiction world. e*I* ran from 2002–2012, and won a FAAn Award in 2009.

As a fan legend and successful fanpolitician Earl had his share of critics and detractors, but for jaw-dropping accusations none approached the level of D. Bruce Berry, who wrote a 38-page rant, A Trip To Hell (1962), about the evils of fandom in general and Earl Kemp in particular. Berry, who also lived in Chicago area, alleged that Earl, wearing a mask, had robbed him on the streets of Chicago on Labor Day night in 1958. This did not take into account that on that date Earl was attending the Worldcon in Los Angeles (South Gate in ’58). Additionally, Berry accused Kemp of railroading him into an insane asylum for three weeks. This became, if nothing else, a collectible zine.

Or considering what happened later, was D. Bruce Berry surpassed by the FBI and Richard Nixon? You may think so after reading Earl’s version of being prosecuted for distributing pornography, “Dickless in San Clemente,” in Michael Dobson’s Random Jottings 8.5.

During the 1960s and ’70s, Earl worked with William Hamling at Greenleaf Classics, publishing erotic paperbacks (quite a few of them written by sf pros under pseudonyms). One of Earl’s great pleasures was the artwork – though probably not for the reason you think. As he wrote in e*I* —

In the 1960’s, after the Porno Factory moved to California and when I was boss, one of my biggest thrills was posing for the covers of some of our books. And, later, when we began using lots of photographs, I enjoyed that one as well for different reasons. The cover artists who worked for us quickly learned of my addiction and would occasionally conspire to involve me a bit more directly.

I remember one particular cover of one of our books that I was very proud of for a number of reasons. I seem to remember it as being an exceptionally good novel and one that I singled out for special handling. It was GC222, Song of Aaron, by Richard Amory, a sort-of sequel to his best-selling Song of the Loon from the previous year.

I had Robert Bonfils, our in-house Art Director, do a wrap-around painting for the cover. It shows two cowboys in the middle of forever (two hills over from Corflu Creek), stopping, dismounting, and stretching. I posed for both cowboys in this painting.

In 1970, not long after the federal government released the Report of the Commission on Obscenity and Pornography, Greenleaf Classics produced a shortened edition called Presidential Report of the Commission on Obscenity and Pornography “replete with the sort of photographs the commission examined.” The commission had been created by the Johnson administration, and among its conclusions said that they found there was “no evidence to date that exposure to explicit sexual materials plays a significant role in the causation of delinquent or criminal behavior among youths or adults.” Nixon was in office by the time the report came out, and his administration emphatically rejected the commission’s findings and recommendations.

Following publication of the Greenleaf Classics version of the report, Kemp and Hamling were prosecuted for “conspiracy to mail obscene material.” At trial, the report as published by Greenleaf was not found to be obscene, but the brochure sent out advertising it for sale was found to be clearly obscene by the jury. Earl was sentenced to a one-year prison sentence (as was Hamling), however, both served only the federal minimum of three months and one day.

Earl’s other output, listed in the Internet SF Database, is three anthologies edited under the Jon Hanlon pseudonym: Death’s Loving Arms & Other Terror Tales (1966), Stories from Doctor Death and Other Terror Tales (1966), and The House of Living Death and Other Terror Tales (1966), and the nonfiction work Sin-A-Rama: Sleaze Sex Paperbacks of the Sixties (2004), co-authored with Brittany A. Daley, Hedi El Kholti, Miriam Linna, and Adam Parfrey.

The Wikipedia includes The Science Fiction Novel, edited by Earl Kemp, Advent:Publishers (1959).

And the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction adds The Memoirs of an Angry Man: The Wit, Wisdom, and Sometimes Humor of The Fourth King of Pornography (2013)

Earl also appeared (sort of) in Milk (2008), about Harvey Milk, the first openly gay person to be elected to public office in California: he was one of the extras. “I’m part of the wallpaper in many scenes. Please applaud loudly when you see the guy in the very loud, 1979 three-piece plaid suit.” (Frank Robinson was another, in one scene noticeably wearing a Greek sailor’s cap and a sweater emblazoned ANITA THE HUN.)

As Earl was ending the run of his amazing fanzine e*I* in 2012, he was presented a Lifetime Achievement Awards at Corflu Glitter, an award created to “salute living fans for their excellent fanac over a long career in Fandom.”

The next year (2013) he was inducted to the First Fandom Hall of Fame.

His survivors include sons Erik Kemp and Earl Terry Kemp.

Earl’s website with many photos is still online here.